Since the return to democratic rule in 1999, several efforts have been made to improve governance and to reform public service in Nigeria. While some of these efforts have recorded some results, some have not. The next administration needs to sustain and accelerate the pace of governance and public service reforms to improve service delivery, citizens’ welfare and overall national development.

In defining governance, we will adopt the definition of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, which defines the concept as “the provision of political, social and economic goods that citizens have a right to expect and that a state has the responsibility to deliver.”1 We will simply define Public Service Reforms as the deliberate actions to continuously improve the structures and processes through which public goods are delivered to citizens.

The trajectory of governance reforms in Nigeria can be roughly divided into three main developmental phases: Foundational; Process-Focused; and Citizen-Centred. We have attempted to delineate the phases with dates, but they do not necessarily all fit neatly into the suggested dates. The delineation by dates is largely illustrative to show a progression in focus.

Post-1999 Reforms, Progress and Challenges

The foundational phase between 1999 and 2007 focused on establishing rules of behaviour and accountability in the public service, being that military rule, which was in place before 1999, operated a command-and-control system that is alien to democratic rule.

The reforms put in place included the establishment of a due process regime and the enactment of the Public Procurement Act in 2007; anticorruption legislations and the establishment of anticorruption agencies; consolidation of salaries and emoluments and the monetisation of fringe benefits; reform of the pensions system from an unaffordable defined pension system to a contributory pension system; and the computerisation of payroll through the Integrated Payroll and Personnel Information System (IPPIS). Most of these reforms were necessarily focused on the operations and mechanics of the public service itself. Apart from telecommunication reforms, pension reforms and some high-level arrests by the anticorruption agencies, many of the reforms did not directly affect the ordinary Nigerian.

The second phase, the process-focused phase between 2008 and 2015, started to be more outward-looking. It saw the commencement of efforts to improve the way things are done and tighten loopholes observed in the foundational phase of the reforms. Some of the reforms undertaken include privatisation of the power sector; justice sector reforms; electoral reforms; initial efforts at improving identity management; Public Financial Management reforms (including the introduction of the Treasury Single Account and the Government Integrated Financial Management Information System, GIFMIS); reform of the banking sector; reform of tax administration; and efforts at improving transparency, with the enactment of the Freedom of Information Act 2011 and the establishment of the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI).

In the third phase from 2016, particularly with the rise in social media usage, the emphasis has started to shift to the experience that citizens have when they encounter government. Some of the reforms undertaken include the ‘Ease of Doing Business’ regime that aims to make it easier to register businesses, obtain business visas, get licences and permits, and facilitate trade. Efforts have also been made to improve consumer protection and improve the country’s resilience to large-scale infectious diseases like Ebola and COVID-19.

It is important to reiterate that the taxonomy used in the preceding paragraphs to delineate the various phases of the reforms is not linear and sequential. For instance, some citizen-focused reforms, such as the initiative against fake and substandard drugs, started well before 2007. Since the introduction of IPPIS in 2006, efforts have subsequently been made to link it to Bank Verification Numbers and National Identity Numbers. Similarly, the national identity management database, established in 2007, did not expand significantly until it was linked to mobile phone numbers in 2020.In essence, reforms are a continuous process. There is no silver bullet which, once fired, obviates the need for further reforms.

Similarly, the various reform efforts have not resulted in linear and sequential improvements. For instance, Nigeria’s ratings on the ease of doing business have improved. Between 2016 and 2020, Nigeria moved up 39 places in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business rankings and was twice recognised as being one of the top 10 countries driving ease of doing business reform.2Aggregate budget performance improved to an impressive 98% in 20203 and the national identity database has expanded from seven million records in 2015 to 97 million records in March 2023.4

Conversely, the gains made in tackling fake and substandard pharmaceuticals have waned, with unapproved pharmaceuticals and sexual enhancement drugs openly offered for sale. The ratings of the country’s anticorruption efforts have been unimpressive since its highest ranking of 136 in 2014. Nigeria is now ranked 150 out of 180 countries.5 Constant electric power remains elusive, and petrol is still not freely available. Also, efforts to reduce the cost of governance have been largely in the realm of rhetoric rather than concrete action.

The Oronsaye Report, submitted in 2012, stated that Nigeria had 547 federal agencies, parastatals and commissions. As of 2021, the Budget Office of the Federation declared that Nigeria had 943 ministries, departments and agencies and 541corporations owned by the

Federal Government.6 Rather than reducing the number of agencies by scrapping and merging some, the government has actually nearly trebled the number of the agencies in the 10 years since the Oronsaye Report, with little discernible improvements in the delivery of public goods.

Efforts have been made to reform the federal civil service, but those efforts have been constrained by wider issues of underinvestment, outdated processes and procedures and limited adoption of technology. Many of the issues bedevilling the civil service, including appointment, promotion, discipline and pay, are outside the control of the Head of the Civil Service of the Federation. There is still no link between government priorities and the job descriptions of individual civil servants, so people are not clear what they are coming to work to do on a Monday morning.

Without focusing on the external levers that affect the civil service, the effects of any civil service reform efforts will be limited. Some state governments have made efforts at governance and public service reforms, but most of these have been sporadic, inconsistent and often half-hearted. There has been a lot more appetite when monetary incentives are offered, as was the case in the hugely successful State Fiscal Transparency, Accountability and Sustainability (SFTAS) programme supported by the World Bank.

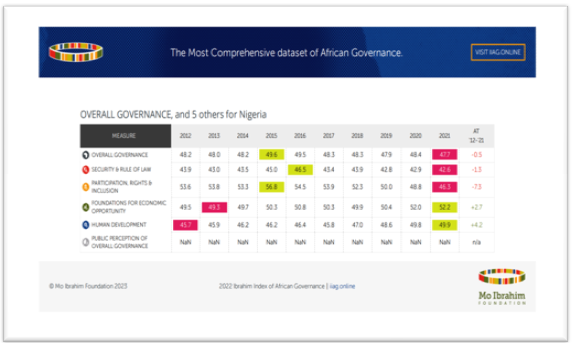

Independent measures of progress on governance reforms show that Nigeria’s performance has been subpar. For the 10 years from 2012 to 2021, Nigeria’s scores on overall governance on the Ibrahim Index of African Governance have consistently averaged 48%.7

Table 1: Nigeria’s performance on the Ibrahim Index of African Governance 2012-2021

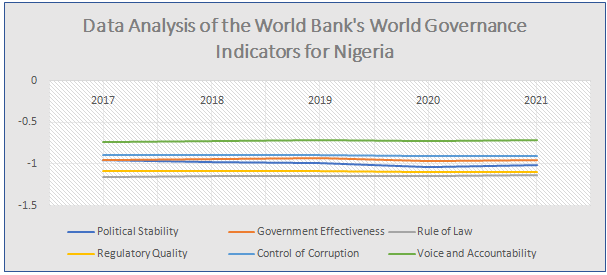

Performance against the Worldwide Governance Indicators for the period between 2017 and 2021 have similarly uninspiring.8

Figure 1: Nigeria’s performance on the Worldwide Governance Indicators 2017-2021

Options For Reinvigorating Governance Reforms

Governance reform is a very wide field, ranging from public policy, through human resource management, to public financial management (budgeting formulation, budget execution, accounting and reporting, debt management, procurement, and external scrutiny and audit), to implementation, execution, monitoring, evaluation and reporting. Consequently, it would be prudent to focus on only a few levers that could have a transformative effect on improving public governance and the delivery of public goods. In this memo, we choose to focus on seven levers: creating a sense of a movement; cutting waste and reducing the cost of governance; rebalancing the public service; raising productivity; improving performance management; connecting with the public; and improving the quality of policymaking.

A sense of a movement

Although several helpful reforms have taken place in Nigeria, what has been missing since 2007 is a sense of a reform movement: a feeling that Nigeria is serious about improving governance for its citizens and that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. This would require the new president to set the tone very early on in the administration that it will no longer be business as usual. The president must rise to the responsibility of reforms through the challenge of personal example, which Chinua Achebe described as the hallmark of true leadership. This would mean showing personal prudence, fiscal responsibility and attempting to gain first-hand knowledge of what citizens experience when they come into contact with their government. This can be done through unscheduled visits to public organisations and ‘mystery shopping’ which entails seeking the provision of public goods while pretending to be an ordinary citizen. The feeling of a movement towards reform will lift the whole ecosystem beyond just focusing on islands of effectiveness.

Reducing the cost of governance and cutting waste

It is important to revisit the Oronsaye Report. Although it is now more than a decade old, most of its recommendations remain valid but have never been implemented. Of all the organisations recommended for abolition or merger, only the National Poverty Eradication Programme (NAPEP) has ever been abolished. In its stead, a new Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development has been created. The impact of the ministry since its creation needs to be evaluated, and the mystery needs to be resolved about the beneficiaries of its interventions and the methodology and data on which their selection was based.

As mentioned earlier, the number of agencies in Nigeria has more than doubled since the Oronsaye Report. However, it is instructive to note that the Oronsaye Report not only proposed organisations that should be abolished or merged but it also listed several organisations that should have stopped receiving government funding for the last 10 years, because they generate revenue or have the capacity to do so. Additionally, the report highlighted some agencies and commissions whose governance arrangements should be streamlined for greater effectiveness. BusinessDay newspaper suggests that implementing the Oronsaye Report could save Nigeria N3.7 trillion!9

Admittedly, abolishing or merging agencies is a difficult task, especially as most of them are established by law, and the issue of potential job losses is always an emotive and politically difficult one. However, the government can implement the recommendations in stages, starting with those organisations that should no longer be getting appropriations from the federal budget. The difficulty of having to propose specific legislation to abolish or merge each individual agency can be addressed with a single Agencies Reform Bill that abolishes or merges the named agencies. That was what was done with the single Petroleum Industry Act that abolished the Department of Petroleum Resources, the Petroleum Products Pricing Regulatory Agency and the Petroleum Equalisation Fund.

(On a related note, there is also an urgent need to tackle oil theft and the vandalisation of oil pipelines. These are best done by deploying technology and visibly sanctioning wrong doers. There is also an urgent need to remove fuel subsidies. Projected to cost $16 billion in 2023, the projected subsidy payments are said to be double the expenditure of all the 36 states of the federation put together.10 Nigeria can simply not afford the level of expenditure to subsidise petrol for urban dweller and neighbouring countries (due to smuggling). Rural dwellers have been paying higher prices for years. The savings from removing petrol subsidies can be ploughed back into human capital development—including education and health—, investing in the civil and public service with better quality personnel and cutting-edge technology, and can also be invested in power and infrastructure development.)

Rebalancing the Public Service

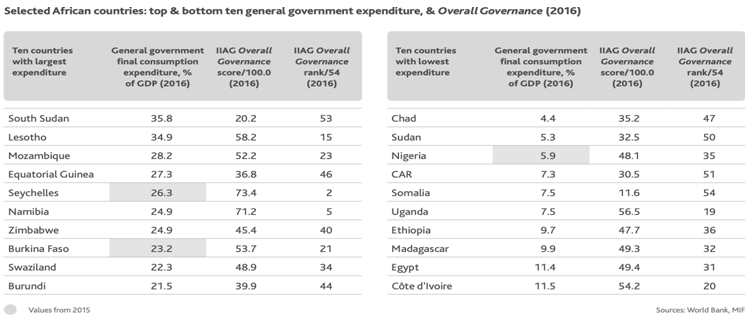

A commonly- held view in Nigeria is that the public service is bloated, and needs to be drastically reduced. This view is not backed by evidence and is incorrect. According to the Federal Government, Nigeria has 720,000 public servants.11 This data was taken from the Integrated Payroll and Personal Information System (IPPIS), the computerised payment system through which public servants get paid their salaries. Some organisations like the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS), the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and the group of entities that formerly made up the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) are not on IPPIS. Even allowing for those that are not on IPPIS and the usual practice by agencies and parastatals of engaging many casual staff and interns, the federal public service is not large by any measure. If we take the unlikely but worst-case scenario that the total numbers would be double what is on IPPIS, that would still be 1,440,000 people. Government employment in the United Kingdom central government wasat 3.6 million as of December 2022, while the total number of UK public servants was estimated to be 5.8 million.12The total number of public servants in Nigeria (federal, state and local government) is estimated at 2.2 million.13Based on 2016 data, Nigeria has one of the lowest general government expenditure in Africa, with general government final consumption accounting for only 5.9% of GDP, compared to other large countries like Ethiopia at 9.7% and Egypt at 11.4% of GDP.14

The issue with the Nigerian public service is that its personnel is poorly distributed, with too many people doing too little, and quite a few people doing too much. There is a need to rebalance the public service to ensure that people are deployed into areas of the greatest need.

The Nigerian public service needs more doctors and other health workers, police officers and teachers. Those public servants that loiter around government ministries and who create the impression that there are too many people with nothing to do should be repurposed to collect more taxes or deployed on the streets to inspect and monitor, in real time, the quality of public services being delivered to citizens.

Raising productivity

Although it is important to reduce the cost of governance and cut waste, there is a minimum level resources required to run a functional government. Therefore, the effort to reduce waste must be complemented by an effort to raise productivity and income. Nigeria must simply produce more. Efforts must be made to raise agricultural and manufacturing output and maximise revenue from solid minerals and the entertainment industry. Nigeria is one of the world leaders in terms of payment platform systems. Government must encourage this industry and the entire information communication and technology industry without getting in their way. It is also vitally important to focus on trade facilitation and to take full advantage of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) regime. The Federal Government recently ranked the Nigeria Customs Service as the least compliant in the ease of doing business regime. Unless the Customs Service is repurposed to focus on trade facilitation, rather than seizures and arrests, the benefits of AfCFTA will remain a distant mirage.

Managing and reporting performance

Performance Management is vitally important. In 2019, the Federal Government identified nine priority areas for the administration and put in place performance indicators and targets for ministries. It also set up a Central Delivery and Coordination Unit (CDCU) in the Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation to track performance against the targets. The results are presented and discussed in annual Presidential Ministerial retreats. This is a commendable practice and should be sustained. However, the citizens tend to experience government through agencies and parastatals than through ministries. There is no equivalent process of setting targets and monitoring them even if just for certain priority agencies and commissions. It would help if something like the existing performance management of ministries is put in place for priority agencies.

Connecting with the public

Government communication has been historically poor in Nigeria. The legacy of military rule in Nigeria still means that many government organisations do not feel the need to communicate and engage with the public. What communication exists is often defensive, combative and reactionary. This creates a credibility gap that means even when good work is being done, public perception is that it is not. As an example, data presented at the 2022 Presidential Ministerial Retreat showed that successful prosecution of corruption cases rose by 55% in 2022, and there was a 103% increase in the number of successful criminal prosecutions. But, on the other hand, citizen awareness dropped from 65% in 2020 to just 12% in 2022. It is little wonder then that public perception of anticorruption efforts continues to decline. Government’s mindset on communications needs to change. The image is as important as the substance and in today’s world of social media misinformation and

disinformation, your work alone no longer speaks for you. You must also speak for your work.

Improving the quality of policymaking

Probably as an enduring overhang of military rule, policies in Nigeria tend to be made with a measure of arrogance. The key ingredients of good policy making such as the use of data and evidence, political economy analysis, cost-benefit analysis, risk-mitigation strategies and contingency planning, and comprehensive stakeholder consultation, are often ignored. A recent example of this poor approach to policy making is the recent CBN cash confiscation fiasco. Conscious effort should be made to ensure that policies that are likely to affect the lives of citizens are thoughtfully developed and that key stakeholders are consulted before they are put in place. The rush to make announcements and think later must be reversed.

Recommendations

To pull the levers that will trigger an acceleration of governance and public service improvements in Nigeria, we make the following recommendations:

- The new president, in words and actions, should create a sense of a reform movement in which the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. He should lead this movement through personal example.

- There is an urgent need to reduce the cost of governance and cut waste. Initiatives here should include implementing the Oronsaye Report in phases and removing petrol subsidy.

- There is a need to rebalance the public service to ensure that personnel are deployed in the areas of greatest need and that future recruitment priorities essential workers like doctors and other health workers, police offices, teachers and quality-of-service inspectors.

- There is a need to raise productivity by facilitating an increase in agricultural and manufacturing output and promoting information and communication technology, particularly with payment systems where Nigeria competes favourably with the best in the world.

- There is a need for enhanced focus on Performance Management. Particularly, it would be necessary to set priority targets at the start of the administration. Ministers should also be issued Ministerial Mandate Letters where the president sets out his personal expectations of each minister upon their appointment. We also recommend that the current performance management system in place for tracking the performance of ministries is sustained and that a similar system for tracking the performance of agencies be put in place.

- Government should focus on strategic and agenda-building communication rather than on reluctant, reactive and defensive communication. Government should have people that are grounded in public policy and strategic communications engaging with the public, explaining government policies in a relatable way and channeling constructive feedback from citizens into improved delivery of public services. The usual practice of engaging journalists principally to defend the administration and attack perceived political foes is now outdated and ineffective.

- Government’s approach to policy making should be more thoughtful, technically sound and consultative. Thoughtless and arrogant policy making inflicts unnecessary hardship on citizens, damages the economy and erodes any goodwill the people may have for the government.

Conclusion

The Nigerian public service has continuously evolved since the return to democratic rule in 1999. From rule-based reforms in the first few years, there is now increasing focus on what the citizens experience when they come into contact with their government. Measured by most indices, public service performance has been weak in aggregate terms. One key reason for this is the lack of a sense of movement: a feeling that the public service is changing for the better and that it is no longer business as usual. If the new President can pull this reform lever, it would be a lot easier to pull the other six catalytic levers set out in this memo for accelerating governance and public service reforms in Nigeria as a whole.