JOE ABAH

How to Accelerate Governance and Public Service Reforms in Nigeria

Since the return to democratic rule in 1999, several efforts have been made to improve governance and to reform public service in Nigeria. While some of these efforts have recorded some results, some have not. The next administration needs to sustain and accelerate the pace of governance and public service reforms to improve service delivery, citizens’ welfare and overall national development.

In defining governance, we will adopt the definition of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, which defines the concept as “the provision of political, social and economic goods that citizens have a right to expect and that a state has the responsibility to deliver.”1 We will simply define Public Service Reforms as the deliberate actions to continuously improve the structures and processes through which public goods are delivered to citizens.

The trajectory of governance reforms in Nigeria can be roughly divided into three main developmental phases: Foundational; Process-Focused; and Citizen-Centred. We have attempted to delineate the phases with dates, but they do not necessarily all fit neatly into the suggested dates. The delineation by dates is largely illustrative to show a progression in focus.

Post-1999 Reforms, Progress and Challenges

The foundational phase between 1999 and 2007 focused on establishing rules of behaviour and accountability in the public service, being that military rule, which was in place before 1999, operated a command-and-control system that is alien to democratic rule.

The reforms put in place included the establishment of a due process regime and the enactment of the Public Procurement Act in 2007; anticorruption legislations and the establishment of anticorruption agencies; consolidation of salaries and emoluments and the monetisation of fringe benefits; reform of the pensions system from an unaffordable defined pension system to a contributory pension system; and the computerisation of payroll through the Integrated Payroll and Personnel Information System (IPPIS). Most of these reforms were necessarily focused on the operations and mechanics of the public service itself. Apart from telecommunication reforms, pension reforms and some high-level arrests by the anticorruption agencies, many of the reforms did not directly affect the ordinary Nigerian.

The second phase, the process-focused phase between 2008 and 2015, started to be more outward-looking. It saw the commencement of efforts to improve the way things are done and tighten loopholes observed in the foundational phase of the reforms. Some of the reforms undertaken include privatisation of the power sector; justice sector reforms; electoral reforms; initial efforts at improving identity management; Public Financial Management reforms (including the introduction of the Treasury Single Account and the Government Integrated Financial Management Information System, GIFMIS); reform of the banking sector; reform of tax administration; and efforts at improving transparency, with the enactment of the Freedom of Information Act 2011 and the establishment of the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI).

In the third phase from 2016, particularly with the rise in social media usage, the emphasis has started to shift to the experience that citizens have when they encounter government. Some of the reforms undertaken include the ‘Ease of Doing Business’ regime that aims to make it easier to register businesses, obtain business visas, get licences and permits, and facilitate trade. Efforts have also been made to improve consumer protection and improve the country’s resilience to large-scale infectious diseases like Ebola and COVID-19.

It is important to reiterate that the taxonomy used in the preceding paragraphs to delineate the various phases of the reforms is not linear and sequential. For instance, some citizen-focused reforms, such as the initiative against fake and substandard drugs, started well before 2007. Since the introduction of IPPIS in 2006, efforts have subsequently been made to link it to Bank Verification Numbers and National Identity Numbers. Similarly, the national identity management database, established in 2007, did not expand significantly until it was linked to mobile phone numbers in 2020.In essence, reforms are a continuous process. There is no silver bullet which, once fired, obviates the need for further reforms.

Similarly, the various reform efforts have not resulted in linear and sequential improvements. For instance, Nigeria’s ratings on the ease of doing business have improved. Between 2016 and 2020, Nigeria moved up 39 places in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business rankings and was twice recognised as being one of the top 10 countries driving ease of doing business reform.2Aggregate budget performance improved to an impressive 98% in 20203 and the national identity database has expanded from seven million records in 2015 to 97 million records in March 2023.4

Conversely, the gains made in tackling fake and substandard pharmaceuticals have waned, with unapproved pharmaceuticals and sexual enhancement drugs openly offered for sale. The ratings of the country’s anticorruption efforts have been unimpressive since its highest ranking of 136 in 2014. Nigeria is now ranked 150 out of 180 countries.5 Constant electric power remains elusive, and petrol is still not freely available. Also, efforts to reduce the cost of governance have been largely in the realm of rhetoric rather than concrete action.

The Oronsaye Report, submitted in 2012, stated that Nigeria had 547 federal agencies, parastatals and commissions. As of 2021, the Budget Office of the Federation declared that Nigeria had 943 ministries, departments and agencies and 541corporations owned by the

Federal Government.6 Rather than reducing the number of agencies by scrapping and merging some, the government has actually nearly trebled the number of the agencies in the 10 years since the Oronsaye Report, with little discernible improvements in the delivery of public goods.

Efforts have been made to reform the federal civil service, but those efforts have been constrained by wider issues of underinvestment, outdated processes and procedures and limited adoption of technology. Many of the issues bedevilling the civil service, including appointment, promotion, discipline and pay, are outside the control of the Head of the Civil Service of the Federation. There is still no link between government priorities and the job descriptions of individual civil servants, so people are not clear what they are coming to work to do on a Monday morning.

Without focusing on the external levers that affect the civil service, the effects of any civil service reform efforts will be limited. Some state governments have made efforts at governance and public service reforms, but most of these have been sporadic, inconsistent and often half-hearted. There has been a lot more appetite when monetary incentives are offered, as was the case in the hugely successful State Fiscal Transparency, Accountability and Sustainability (SFTAS) programme supported by the World Bank.

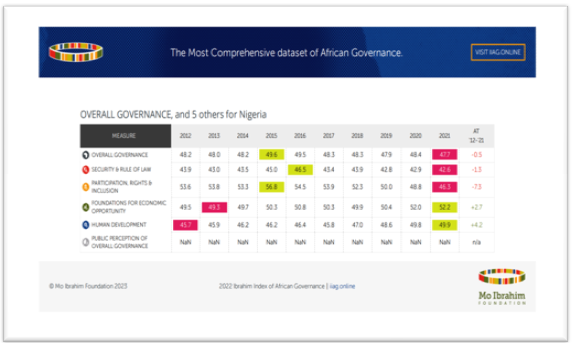

Independent measures of progress on governance reforms show that Nigeria’s performance has been subpar. For the 10 years from 2012 to 2021, Nigeria’s scores on overall governance on the Ibrahim Index of African Governance have consistently averaged 48%.7

Table 1: Nigeria’s performance on the Ibrahim Index of African Governance 2012-2021

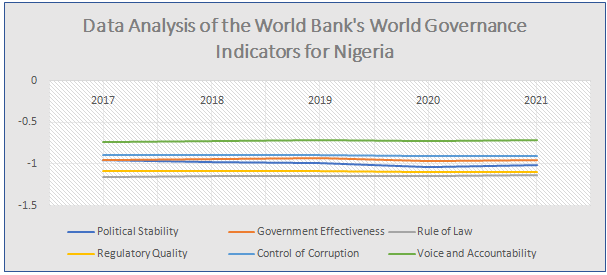

Performance against the Worldwide Governance Indicators for the period between 2017 and 2021 have similarly uninspiring.8

Figure 1: Nigeria’s performance on the Worldwide Governance Indicators 2017-2021

Options For Reinvigorating Governance Reforms

Governance reform is a very wide field, ranging from public policy, through human resource management, to public financial management (budgeting formulation, budget execution, accounting and reporting, debt management, procurement, and external scrutiny and audit), to implementation, execution, monitoring, evaluation and reporting. Consequently, it would be prudent to focus on only a few levers that could have a transformative effect on improving public governance and the delivery of public goods. In this memo, we choose to focus on seven levers: creating a sense of a movement; cutting waste and reducing the cost of governance; rebalancing the public service; raising productivity; improving performance management; connecting with the public; and improving the quality of policymaking.

A sense of a movement

Although several helpful reforms have taken place in Nigeria, what has been missing since 2007 is a sense of a reform movement: a feeling that Nigeria is serious about improving governance for its citizens and that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. This would require the new president to set the tone very early on in the administration that it will no longer be business as usual. The president must rise to the responsibility of reforms through the challenge of personal example, which Chinua Achebe described as the hallmark of true leadership. This would mean showing personal prudence, fiscal responsibility and attempting to gain first-hand knowledge of what citizens experience when they come into contact with their government. This can be done through unscheduled visits to public organisations and ‘mystery shopping’ which entails seeking the provision of public goods while pretending to be an ordinary citizen. The feeling of a movement towards reform will lift the whole ecosystem beyond just focusing on islands of effectiveness.

Reducing the cost of governance and cutting waste

It is important to revisit the Oronsaye Report. Although it is now more than a decade old, most of its recommendations remain valid but have never been implemented. Of all the organisations recommended for abolition or merger, only the National Poverty Eradication Programme (NAPEP) has ever been abolished. In its stead, a new Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development has been created. The impact of the ministry since its creation needs to be evaluated, and the mystery needs to be resolved about the beneficiaries of its interventions and the methodology and data on which their selection was based.

As mentioned earlier, the number of agencies in Nigeria has more than doubled since the Oronsaye Report. However, it is instructive to note that the Oronsaye Report not only proposed organisations that should be abolished or merged but it also listed several organisations that should have stopped receiving government funding for the last 10 years, because they generate revenue or have the capacity to do so. Additionally, the report highlighted some agencies and commissions whose governance arrangements should be streamlined for greater effectiveness. BusinessDay newspaper suggests that implementing the Oronsaye Report could save Nigeria N3.7 trillion!9

Admittedly, abolishing or merging agencies is a difficult task, especially as most of them are established by law, and the issue of potential job losses is always an emotive and politically difficult one. However, the government can implement the recommendations in stages, starting with those organisations that should no longer be getting appropriations from the federal budget. The difficulty of having to propose specific legislation to abolish or merge each individual agency can be addressed with a single Agencies Reform Bill that abolishes or merges the named agencies. That was what was done with the single Petroleum Industry Act that abolished the Department of Petroleum Resources, the Petroleum Products Pricing Regulatory Agency and the Petroleum Equalisation Fund.

(On a related note, there is also an urgent need to tackle oil theft and the vandalisation of oil pipelines. These are best done by deploying technology and visibly sanctioning wrong doers. There is also an urgent need to remove fuel subsidies. Projected to cost $16 billion in 2023, the projected subsidy payments are said to be double the expenditure of all the 36 states of the federation put together.10 Nigeria can simply not afford the level of expenditure to subsidise petrol for urban dweller and neighbouring countries (due to smuggling). Rural dwellers have been paying higher prices for years. The savings from removing petrol subsidies can be ploughed back into human capital development—including education and health—, investing in the civil and public service with better quality personnel and cutting-edge technology, and can also be invested in power and infrastructure development.)

Rebalancing the Public Service

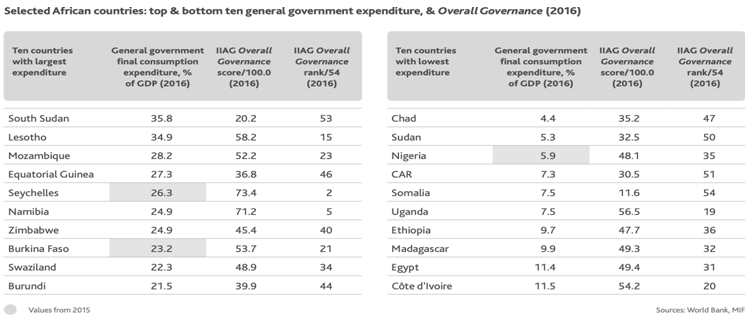

A commonly- held view in Nigeria is that the public service is bloated, and needs to be drastically reduced. This view is not backed by evidence and is incorrect. According to the Federal Government, Nigeria has 720,000 public servants.11 This data was taken from the Integrated Payroll and Personal Information System (IPPIS), the computerised payment system through which public servants get paid their salaries. Some organisations like the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS), the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and the group of entities that formerly made up the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) are not on IPPIS. Even allowing for those that are not on IPPIS and the usual practice by agencies and parastatals of engaging many casual staff and interns, the federal public service is not large by any measure. If we take the unlikely but worst-case scenario that the total numbers would be double what is on IPPIS, that would still be 1,440,000 people. Government employment in the United Kingdom central government wasat 3.6 million as of December 2022, while the total number of UK public servants was estimated to be 5.8 million.12The total number of public servants in Nigeria (federal, state and local government) is estimated at 2.2 million.13Based on 2016 data, Nigeria has one of the lowest general government expenditure in Africa, with general government final consumption accounting for only 5.9% of GDP, compared to other large countries like Ethiopia at 9.7% and Egypt at 11.4% of GDP.14

The issue with the Nigerian public service is that its personnel is poorly distributed, with too many people doing too little, and quite a few people doing too much. There is a need to rebalance the public service to ensure that people are deployed into areas of the greatest need.

The Nigerian public service needs more doctors and other health workers, police officers and teachers. Those public servants that loiter around government ministries and who create the impression that there are too many people with nothing to do should be repurposed to collect more taxes or deployed on the streets to inspect and monitor, in real time, the quality of public services being delivered to citizens.

Raising productivity

Although it is important to reduce the cost of governance and cut waste, there is a minimum level resources required to run a functional government. Therefore, the effort to reduce waste must be complemented by an effort to raise productivity and income. Nigeria must simply produce more. Efforts must be made to raise agricultural and manufacturing output and maximise revenue from solid minerals and the entertainment industry. Nigeria is one of the world leaders in terms of payment platform systems. Government must encourage this industry and the entire information communication and technology industry without getting in their way. It is also vitally important to focus on trade facilitation and to take full advantage of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) regime. The Federal Government recently ranked the Nigeria Customs Service as the least compliant in the ease of doing business regime. Unless the Customs Service is repurposed to focus on trade facilitation, rather than seizures and arrests, the benefits of AfCFTA will remain a distant mirage.

Managing and reporting performance

Performance Management is vitally important. In 2019, the Federal Government identified nine priority areas for the administration and put in place performance indicators and targets for ministries. It also set up a Central Delivery and Coordination Unit (CDCU) in the Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation to track performance against the targets. The results are presented and discussed in annual Presidential Ministerial retreats. This is a commendable practice and should be sustained. However, the citizens tend to experience government through agencies and parastatals than through ministries. There is no equivalent process of setting targets and monitoring them even if just for certain priority agencies and commissions. It would help if something like the existing performance management of ministries is put in place for priority agencies.

Connecting with the public

Government communication has been historically poor in Nigeria. The legacy of military rule in Nigeria still means that many government organisations do not feel the need to communicate and engage with the public. What communication exists is often defensive, combative and reactionary. This creates a credibility gap that means even when good work is being done, public perception is that it is not. As an example, data presented at the 2022 Presidential Ministerial Retreat showed that successful prosecution of corruption cases rose by 55% in 2022, and there was a 103% increase in the number of successful criminal prosecutions. But, on the other hand, citizen awareness dropped from 65% in 2020 to just 12% in 2022. It is little wonder then that public perception of anticorruption efforts continues to decline. Government’s mindset on communications needs to change. The image is as important as the substance and in today’s world of social media misinformation and

disinformation, your work alone no longer speaks for you. You must also speak for your work.

Improving the quality of policymaking

Probably as an enduring overhang of military rule, policies in Nigeria tend to be made with a measure of arrogance. The key ingredients of good policy making such as the use of data and evidence, political economy analysis, cost-benefit analysis, risk-mitigation strategies and contingency planning, and comprehensive stakeholder consultation, are often ignored. A recent example of this poor approach to policy making is the recent CBN cash confiscation fiasco. Conscious effort should be made to ensure that policies that are likely to affect the lives of citizens are thoughtfully developed and that key stakeholders are consulted before they are put in place. The rush to make announcements and think later must be reversed.

Recommendations

To pull the levers that will trigger an acceleration of governance and public service improvements in Nigeria, we make the following recommendations:

- The new president, in words and actions, should create a sense of a reform movement in which the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. He should lead this movement through personal example.

- There is an urgent need to reduce the cost of governance and cut waste. Initiatives here should include implementing the Oronsaye Report in phases and removing petrol subsidy.

- There is a need to rebalance the public service to ensure that personnel are deployed in the areas of greatest need and that future recruitment priorities essential workers like doctors and other health workers, police offices, teachers and quality-of-service inspectors.

- There is a need to raise productivity by facilitating an increase in agricultural and manufacturing output and promoting information and communication technology, particularly with payment systems where Nigeria competes favourably with the best in the world.

- There is a need for enhanced focus on Performance Management. Particularly, it would be necessary to set priority targets at the start of the administration. Ministers should also be issued Ministerial Mandate Letters where the president sets out his personal expectations of each minister upon their appointment. We also recommend that the current performance management system in place for tracking the performance of ministries is sustained and that a similar system for tracking the performance of agencies be put in place.

- Government should focus on strategic and agenda-building communication rather than on reluctant, reactive and defensive communication. Government should have people that are grounded in public policy and strategic communications engaging with the public, explaining government policies in a relatable way and channeling constructive feedback from citizens into improved delivery of public services. The usual practice of engaging journalists principally to defend the administration and attack perceived political foes is now outdated and ineffective.

- Government’s approach to policy making should be more thoughtful, technically sound and consultative. Thoughtless and arrogant policy making inflicts unnecessary hardship on citizens, damages the economy and erodes any goodwill the people may have for the government.

Conclusion

The Nigerian public service has continuously evolved since the return to democratic rule in 1999. From rule-based reforms in the first few years, there is now increasing focus on what the citizens experience when they come into contact with their government. Measured by most indices, public service performance has been weak in aggregate terms. One key reason for this is the lack of a sense of movement: a feeling that the public service is changing for the better and that it is no longer business as usual. If the new President can pull this reform lever, it would be a lot easier to pull the other six catalytic levers set out in this memo for accelerating governance and public service reforms in Nigeria as a whole.

Practical Steps for Effective Implementation of the Oronsaye Report

On 26th February 2024, the Federal Government announced, with great fanfare, that President Bola Tinubu had ordered the implementation of the Oronsaye Panel Report.

Although many news outlets reported that the president had ordered “the full implementation of the Oronsaye Report”1, what the Special Adviser to the President on Policy and Coordination, Ms. Hadiza Bala-Usman, announced was that:

“Our administration has taken a very bold step towards the implementation of aspects2 of the Oronsaye Panel Report which speak to mergers, subsuming, scrapping and relocation of parastatals, agencies and commissions of the Federal Government. This is in line with the need to reduce the cost of governance and ensure that we have streamlined efficiency across the governance value chain.”

She then went on to announce that two organisations will be scrapped; 30 agencies will be merged with each other; nine agencies will be subsumed under existing agencies; and four agencies will be relocated from their current ministries to different ministries. Although the Oronsaye Report of 2012 was aimed at reducing the number of agencies, the Budget Office of the Federation announced that, as of 2021, the Federal Government owned 943 ministries, departments and agencies and 541 corporations.3 It is, therefore, clear that what the government announced in February 2024 was in no way the “full implementation of the Oronsaye Report.”

Some of the agencies affected by government’s announcement last month did not even exist at the time of the Oronsaye Report, e.g., Nigerians in Diaspora Commission and Nigerian Army University, Biu. So, while many aspects of the February 2024 announcement speak to the Oronsaye Report, it can be difficult to find a direct read-across in some cases. Save for the announcement to the press on 26th February, the analysis upon which the decisions were made has not been made public.

On 7th March 2024, the Federal Government inaugurated a 10-member committee to implement, in 12 weeks, the decisions on mergers, abolitions, subsummations and relocations announced in February. Given that majority of the agencies affected are set up by acts of the National Assembly and would require legislative amendment, a 12-week timeframe appears very optimistic. Of particular interest is the case of the Public Complaints Commission that is meant to be subsumed under the National Human Rights Commission. Section 315 of the 1999 Constitution says that nothing in the constitution shall invalidate the Public Complaints Commission Act. The Public Complaints Commission Act itself says that there shall be a Public Complaints Commission. It will be interesting to see how the subsummation will be done without significant disruption to both organisations.

The Many Lives of the Oronsaye Report

First, some background. The ‘Presidential Committee on the Restructuring and Rationalisation of Federal Government Parastatals, Commissions and Agencies’, whose output is popularly known as the Oronsaye Report, was inaugurated on 18August 2011 with the following Terms of Reference:

- To study and review all previous reports/records on the restructuring of Federal Government parastatals and advise on whether they are still relevant.

- To examine the enabling acts of all the Federal agencies, parastatals and commissions and classify them into various sectors.

- To examine critically the mandates of the existing Federal agencies, parastatals and commissions and determine areas of overlap or duplication of functions and make appropriate recommendations to either restructure, merge or scrap them to eliminate such overlaps, duplication or redundancies; and

- To advise on any other matter(s) that is(are) incidental to the foregoing which may be relevant to the desire of government to prune down the cost of governance.

The committee submitted its report in April 2012. In summary, the committee identified 541 government agencies, parastatals and commissions and recommended the reduction of statutory agencies from 263 to 161. It further recommended the abolition of 38 agencies, the merger of 52 agencies and the reversal of 14 departments to ministries. Additionally, it called for the management audit of 89 agencies and the discontinuation of funding to several organisations.

Curiously, it is very difficult to find the actual Oronsaye Report anywhere. Any online search for it is likely to return the 2014 government whitepaper in response to the report and various commentaries on the report, but not the 659-page Oronsaye Report. Interestingly, the Oronsaye Report itself bemoaned the difficulty of obtaining the reports of past restructuring and rationalisation efforts, such as the Joda Report of 1999; the government whitepaper in response to the Joda Report in 2000; and the Ayida Reports of 1995 and 1997.

For such important documents, record-keeping by the Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation should be much better. Once concluded, the reports should also be available online. Under my leadership of the Bureau of Public Service Reforms (BPSR), we ensured that the government ‘White Paper on the Report of the Presidential Committee on Restructuring and Rationalisation of Federal Government Parastatals, Commissions and Agencies’ that was issued in response to the Oronsaye Report was digitised and made available online.4

In the 12 years since the Oronsaye Report was completed, successive governments have periodically announced their intention to implement the report and have set up various committees to update it and bring it up to speed with prevailing realities. However, beyond the announcements and the committees, not much else happens after.

The focus of this policy note is on how the announcement of February 2024 could be implemented. In considering the issues, we would avoid debates about whether one agency was a suitable match for another agency in terms of merger; whether different agencies from the ones announced should have been scrapped or merged; whether other aspects of the Oronsaye Report should have been implemented; or whether the 54 organisations affected by the announcement are sufficient to make any difference (given that, as at 2021, we had 943 ministries, departments and agencies and 541 corporations) or whether any movement at all in this direction is a commendable start. Reasonable people can hold different opinions about these and the current debate in the public space about them is healthy.

Instead of considering these debates here, valid as they are, this note will provide a guide on how to effectively actualise the expressed intentions of the current government. We have chosen this approach, given that, in 2014, the government had published and gazetted a white paper that came to the following unimplemented decisions:

(i) Two new agencies should be created, and one existing agency will require a law to give it legal backing.

(ii) Four agencies and a presidential committee should be abolished.

(iii) Seventeen agencies should be merged to eight.

(iv) The enabling acts of 17 organisations should be amended to incorporate relevant decisions of government.

(v) Twelve organisations should be restructured/reorganised at the board or management levels.

(vi) Two agencies should be transferred to become part of other organisations.

(vii) Nine agencies and 12 River Basin Authorities should be commercialised or privatised over the next five years.

(viii) Seventeen organisations should have periodic staff/management audits.

(ix) Nineteen organisations should cease to receive direct funding from government at various times between 2014 and 2018.

Apart from the fact that many more new agencies were created after 2014, the government did not implement its own gazetted white paper. There have been at least three reviews of the Oronsaye Report and two further draft whitepapers since the 2014 whitepaper. Apart from the scrapping of the National Poverty Education Programme (NAPEP), implementation has been non-existent. But after the scrapping of NAPEP, government has created a National Social Investment Programme and a new Federal Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development to oversee the government’s social investment agenda.

Factors to Consider in Merging and Subsuming Agencies

The merger of ministries is very common in the public sector. Ministries are not set up by law and can be reconfigured at will by the president. Even then, the merger of ministries is often done haphazardly. The announcements are made before any deep thought is given to how to operationalise the announcement. Often, when two ministries are merged, the permanent secretaries remain, and each retain a set of directors, deputy directors and other civil servants. For instance, when the Ministry of Power was merged with the Ministry of Works and Housing, there was a Permanent Secretary for Power and a Permanent Secretary for Works and Housing. As the permanent secretary is the ‘Accounting Officer’ of the ministry and the chief adviser to the minister, it was unclear which of the two permanent secretaries had ultimate authority over budgets, expenditure and staffing.

Conversely, there was initially a Minister of Transport and a Minister of Aviation (Transport) within the same ministry before the Ministry of Aviation was eventually made a standalone ministry during President Muhammadu Buhari’s second term. At the time, it was argued that, unlike others, the Minister of Aviation (Transport) was never announced as a Minister of State and was therefore a full-fledged minister. Both ministers were served by the same permanent secretary who described his situation at the time as that of a woman who had two husbands that did not necessarily get on with each other.

However, with the merger of ministries, governments tend to muddle through until the next reconfiguration. The civil servants remain and there is no talk of job losses. Often, mandates are not formally clarified and approved by the Federal Executive Council and people act more on instincts than with clearly redefined mandates. Save for changes in stationery and websites, not much actually changes.

On the other hand, the merger of agencies is not very common, particularly as most agencies are set up by enabling legislative acts. To merge them, you would need to repeal the laws of the agencies you are merging and enact a new law. In some cases, there may even be a need for constitutional amendment, which is a much difficult undertaking. Mergers are more common in the private sector and there is very little guidance on how to merge public sector parastatals, agencies and commissions. To address this gap, the BPSR under my leadership published two guides: ‘How to Merge and Wind Down Agencies and Parastatals’, published in May 2014; and ‘Guiding Principles for Merging and Restructuring Ministries, Departments and Agencies’5, published in October 2015. This policy note will draw from these two guides without getting into the weeds of what is quite a complicated and technical process.

- Governance Arrangements for the Mergers

Mergers are complex restructuring processes that require time, expertise and planning. Although the government has announced a 10-member implementation committee for this initiative, that body can only look at things superficially. If any progress at all is to be made in the 12 weeks that the committee has been allotted for its assignment, it will be important to put in place a merger committee for each agency that is to be merged. That merger committee will develop a plan for the merger, with a realistic timeframe and budget for implementation. It will be able to get into the details of what is required and then report to the 10-member committee for policy decisions. One of the things that the 10-member committee must provide guidance on is what the purpose of the merger is. Is it to improve service delivery, to raise productivity or just to cut costs? If it is to cut costs, what costs will it cut? Is it feasible that there will really be no job losses as the Minister of Information announced?

Mergers cost money and there is a need to develop a budget and ensure the release of funds. For instance, it was announced that the National Agency for Science and Engineering Infrastricture (NASENI), located in Abuja, is to be merged with the National Centre for Agriculutral Mechanisation (NCAM), located in Ilorin, Kwara State, and the Projects Development Institute (PRODA), located in Enugu. How does one even begin to take an independent inventory of assets or a confirmation of staffing numbers without an allowance for travel between the three organisations? It is not clear whether budgetary provision was made for this limited implementation of the Oronsaye Report. If no budgetary provision was made, it may be necessary to seek a virement to repurpose the 2024 budget of each agency to be merged or to submit a supplementary budget. Alternatively, it is possible to approach donors.

- Audit of Assets

It is very important to immediately carry out an independent inventory of assets in each agency to be merged. Without this, there is real risk of significant asset flight. Even if each agency is asked to produce a list of assets (buildings, vehicles, computers, bank balances, etc) and liabilities on its own, it would need to be independently verified. Otherwise, there is a very real possibility that an entire building or a number of luxury vehicles would simply disappear. It is unlikely that the 10-member committee will be able to conduct this audit by itself. It may have to commission a set of public servants (say, from the Office of the Auditor General for the Federation) or engage external accounting firms to do it. Either way, it will cost money and it take some time.

- Staff Audits

Similar to an audit of assets, it is important to carry out a staff audit in each agency to be merged. Not all agencies are on the Integrated Payroll and Personnel Information System (IPPIS) through which salaries are paid. There is a need to ensure that personnel figures have not been inflated and that people drawing salaries actually exist. Apart from permanent employees, some agencies have hundreds of contract staff and interns that are not on IPPIS. It would be prudent to understand the actual staffing position of each agency to inform decision-making. Undertaking the staff and management audits will take time and cost money.

- Revision of Mandates, Management Arrangements and Organisational Structures

There is a need to review the mandates of all agencies to be merged and develop a consolidated mandate for the new agency that will emerge from the merger. There is also a need to look at the management arrangements and to come up with appropriate human resource levels and a fit-for-purpose organisational structure.

- Staff Utilisation

When organisations are to be merged, there is a need to consider how to handle duplications in functions and what to do with excess personnel. If we use the proposed merger of NASENI, NCAM and PRODA as an example, you will have three agency Chief Executives, three Directors of Finance, three Directors of Human Resources and possibly hundredsof people performing similar roles. With the announcement by the Minister of Information that nobody will lose their jobs as a result of the mergers, how will this siutation be managed? NASENI alone has 11 development institutes, each headed by a Managing Director that reports to an Executive Vice Chairman.

The largest expense of any organisation is its personnel costs, accounting for up to 70% of total costs.6 If the purpose of the mergers is to cut costs, retaining all the staff will ensure that the effort will be an exercise in futility. It is important to consider relieving some of the chief executives of their jobs. It is possible to organise a competition for people in directorate roles, so that the best Director of Finance (for instance) from the agencies to be merged emerges as the Director of Finance for the new entity that will emerge from the merger.

For other staff, it would be necessary to carry out a skills inventory of each staff to see where they could be deployed within the merged entity or whether they have skills that could be helpful in the rest of the public service. Again, this will take a little while and needs to be carefully managed.

Those that were not successful in any competition, or whose skills do not match the mandate of the new organisation, and for whom there are no suitable vacancies in the rest of the public service, can be given enhanced packages to go. If no budgetary provision was made for this, it may be possible to approach some development partners for support or propose a supplementary budget. This will not be quick or easy. Job losses are an emotive issue. The trade unions will pay very close attention to what is done and how. Members of the National Assembly in whose constituencies the agencies are located will be very nervous and will probably have the sympathy of their colleagues.

- New Legislations

Merging two or more organisations that were set up by law into one will require repealing existing acts and putting in place a new establishment act. In developing the new legislation, it will be important to ensure that it is aligned to the ambitions of government and the public now and in the future. For instance, the organisation that emerges from the merger of NASENI, NCAM and PRODA could focus on innovations that promote green energy for homes and to irrigate farms. The process of repeal and enactment will go through the normal legislative process, including first and second readings, committee work, public hearings, passage and harmonisation by the two chambers of the National Assembly, and assent by the president. Needless to say that this will take some time.

- Post Merger Implementation Tasks

We have dwelt more extensively on the pre-implementation tasks because they are the most important and complex but are the ones that are most often ignored. There are many other tasks that are worth mentioning but these can happen as the merger is being done or even when it is completed. For instance, there is a need to look at systems, processes, IT and records integration, staff integration, salary integration (which may undermine the desire to cut costs if the merged entities have different salary structures), integration of organisational cultures, management of stakeholders, knowledge management and public communication.

- Subsummations, Relocations and Scrapping

It was announced that some agencies were to be subsumed under other agencies while some were to be relocated to new ministries, and that a number of agencies would be scrapped. For agencies to be subsumed, most of the pre- and post-implementation tasks set out previously will similarly apply: audit of assets; staff audits; revisions of mandates, management arrangements and organisational structures; and considerations on staff utilisation. There may also be a need to amend legislation, particularly around governance arrangements. For instance, NASENI and PRODA are agencies of the Federal Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, while NCAM is an agency under the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. Whatever power is given to the supervising minister in the existing establishment acts must be transferred to the supervising minister to be named in the new establishment act.

Agencies that are slated for scrapping will need to have their establishment acts repealed and arrangements would need to be made for how to deal with their assests, liabilities and personnel.

Key Recommendations and Conclusion

To ensure that the planned implementation of some parts of the Oronsaye Report does not cause more problems than it tries to address, we make the following recommendations:

- Government should realise that mergers are complex endeavours that require time, expertise, planning and resources.

- Mergers cost money and there is a need to provide a budget for the exercise.

- In addition to the 10-member committee announced by the government, it would be important to set up merger committees for each agency that is to be merged.

- There is a need to sensitise the public about what is realistically achievable in the 12 weeks that the 10-member committee has been given.

- It would be prudent to allow a minimum of six months if things are to be done properly.

- There should be an immediate independent audit of assets, as well as staff audits, of all the agencies affected.

- There should be a review of mandates, management arrangements and organisational strcutures to ensure that the new organisations that emerge are appropriately sized and fit-for-purpose.

- There is a need to rationalise staffing. This should be done sequentially, starting with redeploying people to other parts of the public service where their skills may be needed. However, it would be better to be upfront with the public and the trade unions that some people would have to go. Efforts should be made to offer enhanced packages for people to go, first on volunatry basis.

- The process for subsuming agencies under other agencies, relocating them to new ministries or abolishing them should use the same principles, including audit of assets, staff audits and rationalisation of staff.

- The Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation should improve on its record keeping, particularly for important reports like the Joda, Ayida and Oronsaye reports and ensure that they are posted online for ease of access.

In conclusion, the announcement by the Federal Government that the Federal Executive Council had decided to implement aspects of the Oronsaye Report is welcome. However, the process for merging government agencies is complex and has resource implications. Fortunately, there is helpful guidance that was prepared by BPSR nearly 10 years ago, which is still relevant and applicable. There is a need to ensure that things are done properly so that the effect of the medicine does not end up being worse than the ailment.

By boldly reinventing the public service wheel…

The cliché that one need not reinvent the wheel is intended as a caution against duplicating or recreating that which already exists. To reimagine a perfectly flawless invention is both a futile and valueless effort.

In terms of political society, the invention of the modern bureaucracy is nearly unparalleled in its importance. Like the wheel, its operational intention is to mitigate chaos; and when the bureaucracy functions optimally, unheard and unseen, the effect on any given society is unquantifiable. The British sociologist, Anthony Giddens, in drawing an analogy between the bureaucracy and the wheel, once described the individual worker as a “small wheel” whose ambition is to become a bigger wheel in the bureaucratic machine.

In the case of the Nigerian bureaucracy, something of a reinvention appears necessary. We may have no need to reinstall the bureaucracy anew, but it is now urgent that it be restored to operational efficiency and effectiveness.

For Awolowo, the public service in Nigeria in 1959 was marked by efficiency, incorruptibility, and a sense of loyal and enduring mission among its workers. Modern commentators on the current state of Nigeria’s public service would hardly recognize these attributes.

Where Did It All Go Wrong?

At independence, the Nigerian civil service was widely regarded as one of the best in the commonwealth. Chief Obafemi Awolowo, making his valedictory speech as departing Premier of Western Nigeria at the Western Nigeria House of Assembly in 1959, said of the civil and public service:

“Our civil service is exceedingly efficient, absolutely incorruptible in its upper stratum, and utterly devoted and unstinting in the discharge of its many and onerous duties. For our civil servants, government workers and labourers to bear, uncomplainingly and without breaking down, the heavy and multifarious burdens with which we have in the interest of the public saddled them, is an epic of loyalty and devotion, of physical and mental endurance, and of a sense of mission on their part. From the bottom of my heart, I salute them all.”

For Awolowo, the public service in Nigeria in 1959 was marked by efficiency, incorruptibility, and a sense of loyal and enduring mission among its workers. Modern commentators on the current state of Nigeria’s public service would hardly recognise these attributes.

In 1999, exactly 40 years after Chief Awolowo’s speech, Nigeria returned to democratic rule after a 33-year long hiatus under various military regimes. At all levels, the country’s public service could rightly be regarded as weak and corrupt. In a 2008 document, the Federal Government itself admitted that the public service had “metamorphosed from a manageable, compact, focused, trained, skilled and highly-motivated body into an over-bloated, lopsided, ill-equipped, poorly paid, rudderless institution, lacking in initiative and beset by loss of morale, arbitrariness and corruption.”

The 1999 Constitution, under which Nigeria currently operates and which was bequeathed it by the military has also contributed, whether inadvertently or on purpose, to the dysfunction of the public service.

It is difficult to say precisely when things went wrong. Some observers may suggest that the Nigerian public service was largely functional until the mid-1980s. Others point to the purge of 1975 as the beginning of the destruction of the public service when then military ruler Murtala Mohammed disengaged 10,000 public servants. Yet again, the Dotun Philips report of 1985 that led to Decree No. 43 of 1988 could arguably have been the service’s greatest undoing. That decree effectively destroyed the independence of the civil service by making ministers the chief executives and accounting officers of their own ministries; and by tying the tenure of permanent secretaries (whom it renamed directors-general) to that of the government that appointed them.

Despite the reversal of this policy in 1995, it is not clear the extent to which the civil service has recovered from the overt politicization that the 1988 decree engendered.

While the individual effect of each of these interventions is open to debate, what is undeniable is that military rule had a negative effect on Nigeria’s public service. The arbitrariness and command-and-control nature of military rule does not lend itself well to a cautious, measured bureaucracy that seeks to ensure impersonality, predictability, accountability, and due process.

The 1999 Constitution, under which Nigeria currently operates and which was bequeathed it by the military has also contributed, whether inadvertently or on purpose, to the dysfunction of the public service. As an example, the constitution enshrines a principle known as ‘Federal Character’. Although the explicit aim of this principle is to ensure equitable representation of all parts of the country in public appointments, it has often been used to sacrifice merit at the altar of ethnic and geo-political representation.

Furthermore, the Constitution also centralises all recruitment, promotion and discipline in a Federal Civil Service Commission that has, itself, been accused over the years of undermining the very core values of political neutrality, integrity, accountability and transparency that it was set up to protect.

military rule had a negative effect on Nigeria’s public service. The arbitrariness and command-and-control nature of military rule does not lend itself well to a cautious, measured bureaucracy

From Obasanjo to Buhari

Although efforts at reforming and repositioning the Nigerian civil service date back to colonial rule, it is my view that perhaps the most wide-ranging governance and institutional reform effort thus far in Nigeria’s history has occurred under the Obasanjo administration. Beyond civil service administrative reform, the Obasanjo Reforms encompassed macroeconomic reform, public financial management reform, procurement reform, anticorruption, debt management and development planning reforms.

The impunity that had eroded the public service under the military era required the wholesale establishment of a number of formal and informal rule-based mechanisms. Significantly, the Obasanjo regime introduced the Integrated Payroll and Personnel Information System (IPPIS) and introduced the Tenure Policy to limit the tenure of permanent secretaries and directors to a maximum of 8 years. It also brought in the Monetisation of Fringe-Benefits Policy to consolidate salaries. It sold off government houses to public servants and members of the public to cut the huge maintenance burden on government.

Unlike previous reform efforts, the Obasanjo Reforms were nested in a comprehensive, home-grown, societal development plan known as the National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS). It was these reforms that helped convince the Paris Club of Creditors to grant Nigeria’s debt relief in 2005.

it is worth noting that Nigeria already has many world-class institutions within its public service

The Yar’adua administration that followed went further in developing a National Strategy for Public Service Reforms (NSPSR) in 2008 through the Bureau of Public Service Reforms (BPSR), which had been tasked by the Obasanjo regime to drive the reforms through. The far-sightedness of this strategy is evident in the fact that even the recent reforms of 2016, such as the Treasury Single Account and budgetary reform, had already been articulated by the 2008 Strategy.

The 2008 Strategy was not formally adopted before the unfortunate death of then President Yar’adua. Nevertheless, many of its recommendations continue to be implemented, particularly in the area of public financial management; with such innovations as the Government Integrated Financial Management System (GIFMIS). The GIFMIS is the central payment and accounting system of government that provides central control and monitoring of expenditure and receipts. The system does away with multiple government accounting systems and significantly reduces accounting-related corruption.

Under the administration of former President Goodluck Jonathan, the Bureau of Public Service Reforms updated and refreshed the National Strategy for Public Service Reforms, which it first developed in 2008. Although the fundamental precepts have remained largely unchanged since 2008, the refreshed strategy is currently being updated to reflect the priorities of the current Buhari Administration.

‘Pockets of Effectiveness’ and the Current State of Reforms

The National Strategy is deliberately ambitious in aiming for a world-class public service by 2025. Cynics may scoff at this aim; but it is worth noting that Nigeria already has many world-class institutions within its public service, such as the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control, the Federal Inland Revenue Service, The National Drug Law Enforcement Agency, and the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission. These organisations are able to hold their own against their peers anywhere in the world. The challenge for 2025 is to raise the across-the-board performance of the entire civil service in order that it meets the performance standard that has been set by these ‘pockets of effectiveness’.

The National Strategy for Public Service Reforms (NSPSR) is focused on “Getting Back to Basics”— reinventing the public service wheel in a sense. It sits on 4 Reform Pillars: Governance and Institutional Environment Reform; Socio-Economic Environment Reform; Public Financial Management Reform; and Civil Service Administration Reform. The Strategy is underpinned by a robust monitoring and evaluation framework; with clear, phased, activities, building blocks and target results.

Significantly for a home-grown Nigeria plan, it also identifies risks to its own implementation and sets out mitigating arrangements. It recognises the commonly-held view that one of the problems with Nigeria is not in the planning but in the implementation. To speak honestly, many plans and strategies in Nigeria are inherently un-implementable, precisely because they do not factor in politics, costs, delivery capability and risks. Over the last 7 years, the NSPSR has continually been implemented, even without formal Federal Executive Council approval, precisely because it considered risks to its own implementation and devised strategies to mitigate those risks.

The effect of prioritizing efficiency, performance, service delivery, anticorruption and reinstalling a sense of mission into Nigeria’s civil and public service is to aim at a world-class service by 2025

Reform strategies like the NSPSR, which target the entire government structure are, of course, prone to over-ambition and a blurring of focus. For this reason, the National Steering Committee on Public Service Reforms, chaired by the Secretary to the Government of the Federation, with the Bureau of Public Service Reform as its technical secretariat, has prioritised the following levers: Performance Management; Pay Reform; Rationalisation of Agencies and Parastatals; Restructuring of Ministries; Renewed Focus on Service Delivery; and Budgetary System Reform. Focusing on these areas will have a catalysing effect on the rest of the system

As a direct result of this prioritization, the Federal Government has pushed through the full implementation of the Treasury Single Account; it has also directed that the Integrated Payroll and Personnel Information System should be fully rolled out to the entire public sector; it has commenced the restructuring of ministries; and is undertaking a comprehensive review of the Oronsaye report and the government’s White Paper in response to it.

The Oronsaye report had recommended that the government should scrap 102 statutory agencies, abolish 38 agencies not set up by legal statute, merge 52 existing agencies, revert 15 agencies to departments in relevant ministries and discontinue government funding for professional bodies and councils. The report had enumerated 541 federal government agencies, parastatals and commissions as part of its terms of reference.

The government has also introduced the Zero-Based Budgeting system; although it is fair to say that this change in the budgetary system has had significant teething problems. The expectation is that the 2017 budget will learn lessons from 2016 and be very much improved.

The effect of prioritising efficiency, performance, service delivery, anticorruption and reinstalling a sense of mission into Nigeria’s civil and public service is to aim at a world-class service by 2025. By boldly reinventing the public service wheel, our goal is a return to 1959 and to the kind of bureaucracy that Chief Awolowo would be proud to describe afresh.

Dr Joe Abah is a Nigerian national. He is the Director-General of the Bureau of Public Service Reforms, The Presidency, Nigeria. He is also a Visiting Lecturer at the Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, Maastricht University, the Netherlands.

TAKING KADUNA FROM GOOD TO GREAT: THE CHALLENGE OF PERSONAL EXAMPLE

I am greatly honoured to have been asked to deliver this year’s Inauguration Lecture. The Kaduna Inauguration Lecture of 2015 was delivered by the late, great Professor Pius Adesanmi. His address was titled: “El Rufai and the Challenge of Building Kaduna in a Day With One Kobo.” He concluded his address with the words “To be continued.” Before we continue, may I please seek the indulgence of His Excellency the Governor of Kaduna State for us all to rise and observe a moment’s silence in honour of the memory of Professor Pius Adebola Adesanmi.

May his soul rest in peace!

In setting out the challenge before Governor El-rufai in 2015, Professor Adesanmi posited that there is no option of failure, no reasonable margin of error, and no latitude for mediocrity and unspectacular performance. While a leader can take reasonable steps to guard against mediocrity and unspectacular performance, he or she cannot guarantee that everything that they do will succeed as planned and that there will be no failure. Also, to deny a leader any margin of error is to expect of them the omniscience that only God Almighty possesses. Having said that, Nigerians are tired of potential that never seems to translate into tangible improvements in the lives of citizens. They are tired of the “sleeping giant” epithet. They are tired of the excuses. They want their potential realized now, especially as other countries with less resources are beginning to realise theirs. This, I believe, is what Professor Adesanmi was trying to convey in his inimitable style.

However, although it is my firm belief that a leader that has the will, the support base and the passion to drive change can do so, regardless of the constraints in the environment, I also believe that it will be foolhardy to ignore the intricate challenges of the environment in which the desired change is meant to occur. I will use a recent real-life event to illustrate this point. I am currently from Ebonyi State. I use the term “currently” advisedly. This is because during my lifetime, I have come from Eastern Region, then East Central State, then Imo State, then Abia State, and now Ebonyi State. If, at some point, a sixth state is created in the South East of Nigeria, my village is expected to be in the new state. Funnily enough, I have never actually lived in Ebonyi State. I have never paid taxes there.

My being from Ebonyi State does not affect the price of rice in the market, although we do produce the best rice in the country. It only becomes relevant the moment there is any sharing to be done at national level. In such a case, I would be expected to be quick to claim my Ebonyi indigene-ship over and above those that have lived and worked in Ebonyi all their lives, have paid taxes there, and are directly affected by Ebonyi local governance and politics. This is why I am firmly in support of the Kaduna policy of Equal Citizenship that abolishes the indigene/ settler dichotomy. You are really a citizen of where you live and pay your taxes. It is the policy of that environment that directly affects your daily life. I applaud Governor el-Rufai for his courage in putting this policy in place and hope that it is carried into a review of the 1999 Constitution as soon as possible.

Similar to the concept of Equal Citizenship is the notion that anybody who can be of value should be invited to contribute the value that they have in order to build society, regardless of where they come from. That is why developed nations like the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom have immigration schemes through which they encourage the brightest and the best to lend their talent to nation building. It is for this same reason that I am honoured to have been invited to interact with Kaduna’s Kashim Ibrahim Fellows last year. It is for this same reason that I am here today, being given the great honour of delivering this inauguration lecture. It is also the same reason why Governor-Elect Emeka Ihedioha of Imo State invited me to join his Transition Technical Committee to advise him on issues of ‘Good Governance’, although I am from Ebonyi…currently. Let me now relay to you a recent incidence that occurred as part of that assignment, to provide an insight into why I think that context matters.

The Secretariat of the Imo Transition Technical Committee, of which I am a member, proposed a plenary meeting to review the reports of the various subcommittees. All members of the Committee had been formed into a broadcast-only WhatsApp group where comments and discussions were not allowed. If you had any issue with a broadcast message, you were supposed to contact the Secretariat by phone or email. By the way, someone once said that if you want to know how difficult it is to govern people, open a WhatsApp group and ask people not to post things that are irrelevant to the objectives of the group. You should then sit back and count how many people post irrelevant things and say “Apologies, posted in error” only after someone complains. They tend not to delete the offending post, so was it really posted in error? Anyway, I digress.

Given the wide range of issues to be covered that weekend, the Secretariat of the Imo Transition Technical Committee announced that the meetings will happen throughout Saturday and also on Sunday afternoon. Before long, a huge furore had broken out. Someone said “We are Christians. It is very wrong and insensitive to schedule meetings on a Sunday.” Another person countered: “The future of the people of Imo State is superior to any religious obligations. Sunday is just an ordinary day.” A third commentator said “While I won’t mind working on a Sunday, I don’t agree that Sunday is just an ordinary day. It is a day that Christians set aside to worship God.” He had put the “just an ordinary day” part of his sentence in Capital letters. Then it turned into a free-for-all. You got comments like “I beg to disagree. God first”; another said “Oh my God! We must worship God on Sunday. Imo State needs God now more than ever before to survive”; and yet another said “Please don’t go there! Imo people are religious people and will be most unhappy with you.”

I observed all these with amusement and some sadness and discussed it with a friend of mine that was visiting me at the time and he said that he agreed with them. I asked him: “What about Muslims that worship on Fridays and Jews that worship on Saturdays? Should we not have any meetings on those days?” He said “That is them now. They are different from us.” I said “Seventh-Day Adventists are Christians, just like us. They worship on Saturdays.” A loud silence ensued, and then he came back with “Yeah, but how many are they?” I held my peace. After all, Democracy was described by the French historian and political theorist, Alexis de Tocqueville, as “The Tyranny of the Majority.” I will return to this point later in the lecture.

Then as the WhatsApp exchanges continued, somebody in the WhatsApp group raised the point that all that the Secretariat was trying to arrange was a family meeting. He said that Igbos all over the world, including those in Imo State, hold their town union meetings on Sunday afternoons to discuss issues affecting their communities. If town union meetings could happen on Sundays without offending our Christian values, why couldn’t a meeting that is focused on the wellbeing of Imo State as a whole hold on a Sunday? Would the Governor not have to work on Sundays when he is in office because he is a Christian? By the time that this comment came, the Secretariat had already capitulated and announced that the meeting will now be compressed to hold only on Saturday. Sanctimony had triumphed over logic and common interest. How do you lead a people like these, with what Professor Adesanmi had described as no option of failure, no reasonable margin of error, and no latitude for mediocrity and unspectacular performance? Who wants to be a Governor? Well, one governor is quoted as saying “I will be the first to concede and I want to tell all that want to be governor that it is not an easy job…I want to run away.” The name of that governor is Nasir Ahmad el-Rufai!

A lot has been achieved in Kaduna over the last four years. In the area of Education, a Primary School Feeding Programme is in place and there is a Free Basic Education Policy. There have been reforms on Teacher Quality, including a 30% salary increase for teachers in the rural areas and a 28% increase in the salary of teachers in urban areas. Before the salary increases were implemented, about 22,000 unqualified teachers were disengaged and replaced with better-qualified ones. I remember personally coming under attack for supporting this initiative. As usual, Nigerians raised the emotive issue of job losses and the hardship that the disengagement will cause to the families of those disengaged. Nobody worried about the hardship and lack of employability that substandard education is causing to the children, their families and the society at large. I found it incredulous that anyone believed that we should be teaching primary school teachers how to read and write!

In the area of healthcare, the Primary Healthcare Under One Roof initiative was put in place, as was a Contributory Health Insurance Scheme. A number of health facilities were also refurbished and upgraded. In terms of Social Protection and Welfare, a Child Protection and Welfare Law and an Anti-Hawking and Begging Law were enacted. A Kaduna State Women Empowerment Fund Scheme was also put in place.

With regards to Governance reforms, Kaduna State put in place the Treasury Single Account and adopted the Zero-Base Budgeting approach in its budget preparation. It also domesticated the Fiscal Responsibility Law and passed a Public Finance Control and Management Law. It is instructive that, at the National level, we are still operating the 1958 Finance (Control and Management) Act without amendment. Ministries in Kaduna were streamlined, a programme of Pension Reforms was undertaken and internally generated revenue increased by nearly 70% compared to 2015. A number of bright young people were also appointed to bring energy and fresh ideas into governance. It is worth pointing out that many of them are not from Kaduna State.

In the area of Economic Development, Kaduna ranked first in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business rankings with regards to Registering a Property and Enforcing Contracts. The annual Kaduna Investment Summit has become a popular means through which needed investment has flowed into the state, leading to a near 12% jump in the GDP of the state. It was announced a couple of days ago that the Kaduna State Government had attracted $400 million in new investments in the last 4 years.

Despite the formation of a Peace Commission, security remains a challenge, with killings in various parts of the state. A number of communities were attacked by bandits and, at various times, the Kaduna to Abuja road became one of the most dangerous roads in the country with regards to robbery and kidnapping. Ethnic and religious clashes also led to the death of many citizens, including citizens of other countries.

I have simply stated the facts, without forming a judgment on the performance of the government in the last 4 years. I believe that the people of Kaduna State formed that judgment with their votes on the 9th of March 2019. Re-electing this government for another four years, despite the challenges with security and the difficult decisions like disengaging 22,000 teachers suggests that they saw something good in what the government is doing. Our task now is how to take Kaduna from Good to Great.

In Jim Collins’s book “Good to Great”, he discussed several ingredients that are necessary to move an organisation is to move from being a good organization to a great organization. Of course, he was writing about private sector organisations but many lessons from his book are also applicable to the public sector. We can summarise Collins’s 300-page book by saying that it calls for Discipline. Disciplined People, Disciplined Thought and Disciplined Action. Discipline is therefore a key attribute in driving an organization from good to great.

In his seminal work, ‘The Trouble With Nigeria’, Chinua Achebe used a football analogy to reflect on why Nigeria never seems able to, as he calls it, “present its first 11.” The quote that is very often cited is where he says that there is basically nothing wrong with Nigeria and that the trouble with Nigeria is simply and squarely a failure of leadership. I will not focus on that part. I would rather focus on a part of the same statement that is often not cited. That is where he says that “The Nigerian problem is the unwillingness or inability of its leaders to rise to the responsibility, to the challenge of personal example which are the hallmarks of true leadership.” It is on this more difficult aspect, the challenge of personal example, that our lecture must now focus.

To start this part of the discourse, I would invite you to accompany me back to Imo State. The Chairman of my ‘Good Governance’ subcommittee is Honourable Justice Paul Onumajulu, former Chief Justice of Imo State, a cerebral, wise, jovial but firm man. In a discussion with him on leadership, he proposed that a leader must score 6 Credits and one ‘F’ if he wants to be great. Like you, I didn’t, at first, understand what he was talking about. Why not 8 ‘A’s? Why an ‘F’? It started to make sense as soon as he began to explain what he meant. The first of his 6 Credits is Capacity. He posits that a great leader must have the mental ability to lead. She should really have above average intelligence and if she is not born with it, she must work hard to acquire it through diligent study. The second is Capability, which he describes as the physical strength to work long hours and be visible to the people. The third ‘C’ is Credibility. This connotes the need to be sincere and trustworthy. The leader must ensure that his word is his bond and that he is not asking people to do things that he himself is not doing.

The fourth ‘C’ is Courage: the quality of fearlessness and the ability to take difficult decisions in the interest of his people. As the Greek philosopher Sophocles once said: “I have nothing but contempt for the kind of governor who is afraid, for whatever reason, to follow the course that he knows is best for the state.” The 5th ‘C’ is Conscience: having one’s actions guided at all times by choosing right over wrong. As Mahatma Gandhi once said “There is a higher court than the courts of justice, and that is the court of conscience. It supersedes all other courts.” The 6th and final ‘C’ is Consistency: the realization that, as Aristotle once said; “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.” The Retired Chief Justice included an ‘F’ as part of the requirements for great leadership. An ‘F’ may initially sound like failure but it actually stands for Fear of God. It is the realisation that we are not only answerable for our actions in this life but also in the afterlife.

Because Kaduna is a microcosm of Nigeria, I will add three additional credits. The first ‘C’ is Compassion. A few days ago, UK Prime Minister Theresa May resigned in tears after three difficult years as Prime Minister. Many commentators did not feel sorry for her because they felt that she lacked empathy and was unable to show compassion when she was required to do so. An example was when she displayed no emotion whatsoever in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire and when she laughed in parliament when the issue of rising child poverty in the UK was raised. A leader cannot be hard all the time. They must be able to show compassion when a tragedy occurs or when people are suffering.

The second ‘C’ I will add is Circumspection. In leading people, it is often not enough to be right. The wrong word at the wrong time to the wrong audience can trigger consequences of unimaginable proportions. That is why we must understand the decision of the Secretariat of the Imo Transition Technical Committee not to go ahead with a meeting on Sunday afternoon. Once religion had become involved, the Secretariat risked organising a meeting that many members would not attend or would attend principally to express their displeasure. Not much would have been achieved and the Secretariat would have acquired a reputation for insensitivity. That the Secretariat listened to the cacophony and adjusted its plans was not a sign of weakness but a lesson in leading opinionated people. Religion and reason do not always mix well. That is why a leader must be circumspect around issues of religion. Logic and common-sense are often not enough.

The final ‘C’ is Communication. A leader must engage with the citizens at all times. In this era of fake news and wild unsubstantiated allegations, government communication must be proactive, rather than defensive. The government must put forward and constantly explain its own agenda before its detractors plant falsehoods in the minds of citizens. Once the falsehood is allowed to take hold in the minds of citizens, it becomes a certain version of the truth to many. Communication is different from Information though. While Information is unidirectional, Communication is a two-way process that requires the ability to listen and to take in the opinions of others.

Additionally, there is a need to redouble all efforts on improving security. The nexus between Security, Peace and Development is clear. There can be no development without peace and security, and no peace and security without development. It is additionally important to protect minority rights and guard against the tyranny of the majority. A lot of conflicts in the world today started as a result of a feeling of grievance.

To take a society from good to great then, the challenge of personal example which is the hallmark of true leadership demands Discipline, Capacity, Capability, Credibility, Courage, Conscience, Consistency, Compassion, Circumspection, Communication and Fear of God. If you have keeping tabs on the ‘Credits’, it requires 9 Credits, 1 ‘D’ and 1 ‘F.’

What about the people being led though? What is required of them if the state is to move from good to great? Well, everybody wants change but nobody wants to change. We all want change but many of us do not have the appetite for the difficult decisions required to bring about a better outcome for everyone. We cannot constantly complain about the state of our nation in one breath and then criticise the tough decisions that are taken to address the issues we are complaining about in another breath. Governance is not a beauty contest. We cannot eat our cakes and have it.

Having said that, you will probably have noticed what sounds like a contradiction. On the one hand, I had said that a leader that wants to lead a society to greatness must have the courage to take tough decisions. On the other hand, I have also said that leader must be circumspect around certain issues and show compassion, and that being right is often not enough. One weakness of the social sciences is that they sometimes try too hard to resemble the physical sciences, like physics that has seemingly-immutable laws. Newton’s Third Law states that “For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.” This is true in the physical sciences but is not necessarily the case in human relations.

Human beings are not machines and the world is not a sterile laboratory. Sometimes, you need impetuous behaviour. At other times you need to be circumspect. As Machiavelli said “A man who is circumspect, when circumstances demand impetuous behaviour, is unequal to the task, and so he comes to grief.” On the other hand, Mahatma Gandhi said: “When restraint and courtesy are added to strength, the latter becomes irresistible.” The skill of the great leader is to know when to be impetuous and when to be circumspect. The human element that challenges Newtons Law of Action and Reaction is perhaps best espoused by the Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, Victor Frankle. He said “Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.” If that stimulus is from social media, it is in that space that the leader should have his phone taken away from him to prevent him from tweeting in the heat of the moment.

Taking Kaduna from Good to Great therefore requires much more than the technical excellence that Kaduna is beginning to be known for. It goes beyond the courage to do the right thing that Governor el-Rufai has always been known for. It requires of everyone in the Kaduna State Government the kind of leadership that rises up to the responsibility, to the challenge of personal example which are the hallmarks of true leadership. That challenge of personal example is what Governor el-Rufai has demonstrated by committing to sending his own son to a public school in Kaduna State. It is my expectation that everyone in a leadership position in the Kaduna State Government will similarly rise to the responsibility, this challenge of personal example.